Hong Kong and Arunachal Pradesh as double-edged swords in China’s national identity project

Introduction

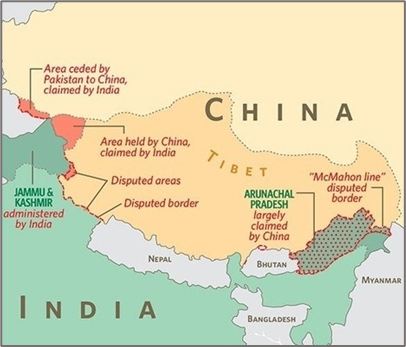

The British Empire, with its colonies and mandates in the five continents, can be considered one of the largest and most important ones in history, not only due to its territorial expansion but also due to the political and cultural influence it had in the areas it held. Yet, more interesting and relevant to this paper is the impact, legacy, and controversies created after these territories achieved independence and the British left. Some clear examples of this are the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, still going on today, the Suez Crisis, and the Falklands War. Specifically, in Asia, we find two main events originated by the British: the Sino-Indian War of 1962 and its aftermath, and Hong Kong’s status until today. In the first case, we can find the cause of the modern conflict in the McMahon Line, an artificial frontier proposed by the colonial administrator, Henry McMahon, between the Tibetan region of China and India’s northeast region called Arunachal Pradesh.

In the second case, it was the Opium Wars in the 1840s, the 99-year lease signed in 1898, and the signature by British Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, and Chinese Premier, Deng Xiaoping, of a Joint Declaration in 1984, which prorogated the latter by 50 years, until 2047, the main causes of the confrontations going on today in the peninsula/island. Through a brief explanation of these two events, this short paper will try to prove that the reason behind China’s interest in having sovereignty over the Arunachal Pradesh area is, in a nutshell, the rejection of playing by the rules that a western, former colonizing state, imposed, in this case, through the McMahon Line. Yet, as it will be analyzed in the conclusion, it is not about the line itself but about what it represents to China’s national identity. Tibet, home to the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan Buddhists, is to China an important part of its essence and, after the “100 years of humiliation”, they are not willing to give it up. Furthermore, if China accepted this area as Indian, accepting the British delineation as legitimate and, therefore, succumbing again into being humiliated by the West and India, it would also have to grant Hongkongers their demands.

Hong Kong’s status: “one country, two systems”

The first decades of the 19th century were very lucrative for British merchants thanks to the goods produced in China such as porcelain, silks, and tea, and then sold in the metropolis. However, the Chinese were not buying British products and would only sell their produce in exchange for silver, causing silver to leave Britain. To stop this, British merchants, especially the East India Company, started smuggling Indian opium into China, demanding silver in exchange for it. The addiction to this drug throughout the mid-1820s was causing very serious social and economic disruption, making the Chinese confiscate and destroy it. Tensions grew until the First Opium War erupted in 1840, resulting in a victory for the British under the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842 which, aside from paying a large indemnity, the Chinese were obliged to give Hong Kong to the British. This was the start of a period known in China as the Century of Humiliation, a very important concept that will be treated towards the end of the paper. Following the Treaty of Nanjing, tensions escalated into the Second Opium War, also won by the Western powers. However, due to security concerns over the important port of Hong Kong, the Crown decided in 1898 to give the island in a 99-year legally binding lease, supposedly ending in 1997.

Fast-forwarding 86 years, 1984 was a crucial year in the development of Hong Kong’s status. After lengthy negotiations, Margaret Thatcher and Deng Xiaoping finally signed a Joint Declaration, which established that the island would return to China on July 1st, 1997 with two main concepts as requirements, under the umbrella of “one country, two systems” rule: first, Hong Kong would keep the capitalist system it had been enjoying and, second, included in Hong Kong’s “constitution”, the Basic Law, it would keep its high degree of autonomy, including its own judicial, executive, and legislative powers. However, it did not include any legally binding clause stating the consequences of not respecting this autonomy. In fact, growing influence from Beijing over recent years has been blurring off its competence limits on the island, leading to today’s tensions. In a nutshell, amendment proposals for Hong Kong’s extradition law have been worrying the locals for one main reason: mainland China could use it to arbitrarily detain and imprison people that openly dissent with the government (since Hong Kong enjoyed freedom of press, religious and political beliefs, etc.). It would also apply retroactively, meaning, “thousands of people who may have angered [Beijing] with a supposed past crime could be at risk of facing trial there.”

Sino-Indian War: Arunachal Pradesh’s symbol as the last remains of British Imperialism

The year 1914 must not only be remembered as the year when World War I erupted but also as the one that strained modern Sino-Indian relations, with Tibet in the middle, until today. To get a clear and synthesized picture of the conflict we must go back to the Simla Convention, a treaty signed by Great Britain, China, and Tibet so as to divide Tibet into “Outer Tibet,” which would be ruled by the Tibetan Government through the Holy City of Lhasa, under Chinese suzerainty, and “Inner Tibet,” under direct Chinese rule. However, it imposed a borderline between the two countries, India and China, that would not be accepted by the Chinese on the basis that Tibet was not a sovereign country with the power to sign a treaty such as this one. This frontier line would be later known as the McMahon Line, only agreed upon by the British and Tibet. And, indeed, it would be one of the main reasons for the 1962 Sino-Indian War. After years of territorial tensions in their common frontier, comes and goes of peace and minor battles, the two Asian countries fought a one-month war, ending with an overwhelming Chinese victory, mostly due to two reasons: first, Prime Minister Nehru’s passivity and overconfidence that the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) would not attack the military posts, together with his famous Forward Policy, consisting on military reinforcements established along the McMahon Line, and, second, China’s vision of a once-again united nation.

Xi’s Chinese Dream

It is, in fact, national identity what connects the Hong Kong situation with the Sino-Indian War. Despite their apparent disconnection, they are more related to each other than it may seem, and it will be the previously mentioned “Century of Humiliation” the key to understanding it. We can start counting these one hundred years from 1839, the First Opium War. It wouldn’t be until the end of the civil war and the creation of the modern People’s Republic of China in 1949, that the Chinese would have the ‘independence’ to decide for themselves. This century was characterized by western and Japanese colonialism, unfair treaties, and failed revolutions, all under the frustrated dream of becoming the nation they had been in the past, the “country of the middle” (中国) that everyone around wanted to imitate, the nation that had given the world the most important non-western philosophers and religions. Under the rule of Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, and Liu Shaoqi, three nationalists with “Chinese Socialism” as their flag, who took on the task of bringing a prosperity-oriented system never seen before in the world, combining their Marxist-Leninist ideology with economic policies that would try to improve the lives of their citizens, China started to unify their identity to work together towards a common goal. In Mao’s own words, in one of his writings regarding the McMahon Line and the pre-Sino-Indian conflict, he said that “the conflict was not about the boundary or territory but about Tibet.” In addition to the fact that the McMahon Line was created and enforced by one of the main humiliators, we see in Tibet part of the lost China that these twentieth-century leaders were trying to recover. And is Xi Jinping who, today, is bringing back these values with his own nuance: “the Chinese Dream,” one of the pillars of his cabinet since 2013, hand in hand with “the great renewal,” clearly reflected in the Belt and Road Initiative. Following Mao’s logic, President Xi’s policies and behavior towards the Hong Kong riots and protests do not originate from the desire to repress those that think and act against the government’s actions. Instead, he, along with the party, thinks that only through these measures will unity be a reality again.

The Opium Wars and the Nanjing Treaty of 1942, among many other events throughout the century of humiliation, are still unconsciously present in the common Chinese imaginary and, having only passed seventy years since its end in 1949, it represents the moment in which they were told what to do. Thus, going back to the main hypothesis, China, in their great project to rebuild itself into, what we could call, the greatest power Asia and even the world has ever seen, cannot let Hong Kong, Arunachal Pradesh, and Aksai Chin (a strategic area in the northeastern part of Jammu and Kashmir which would take another essay to understand) to be independent of the mainland. We must not see this move with the eyes of a westerner, thinking that President Xi is only trying to establish a dictatorship-like state, but trying to understand China’s recent history. In their mind, Hongkongers’ protests are directly connected with the corrupt western ideas of self-determination and capitalism and, at all costs, the government must protect its citizens from it. If the government finally gave up its sovereignty in Aksai Chin and Arunachal Pradesh, not only the islanders would have a renewed hope of real and ultimate independence, but also many regions in Central Asia, especially in Inner Asia, that have been seeking independence for more than half a century, such as the Uyghurs, the Tibetans, the people in Jammu and Kashmir, etc., would stand up for their ‘right. In fact, we see these same problems in Europe since, if, for example, Spain accepted Cataluña as independent, many regions throughout the continent such as Alsace and Bavaria.

Conclusion

To conclude, at a 70th-anniversary celebration of the founding of the People’s Republic of China in September 2019, the PRC’s president stressed the idea of being loyal to the ‘one country, two systems’ model, letting “the people of Hong Kong govern Hong Kong, and the people of Macao govern Macao.” After having understood what’s behind this conflict, these words come as a reminder of his ultimate goal, also noted in his speech, that “we should hold high the banner of peace, development, cooperation and win-win, follow a path of peaceful development, adhere to opening up, and work with people from all other countries to build a community with a shared future for humanity, making the sunlight of peace and development shine brightly all over the globe.” Therefore, before judging China’s intentions as evil, we should try to understand their historical point of view and see that, above all, all he and the Chinese citizenship want is peace and development, looking for a peaceful win-win strategy with the world, but especially with its Asian neighbors. So, when it comes to India, Xi should go back to the famous Sino-Indian relations catchphrase of “Hindi-Chini Bhai-Bhai,” “Indians and Chinese are brothers,” and try to convince Modi that he should let aside his strict nationalist policies (which are making the Indians and the Chinese to have a very unfavorable view of each other ), supported by the West and, especially, the United States, for the good of Asia and its citizens’ wellbeing.